How phonetic is English?

How phonetic is English?

The term “phonics” is frequently used interchangeably with reading instruction, so it’s understandable that many people believe English can be reliably “sounded out.” Ever since alphabets were first invented, alphabetic languages have used letters to represent the sounds in words. The easiest alphabetic languages to learn are those, such as Italian, that use one grapheme (a single letter or a letter combination) for each phoneme (the smallest sound unit in a language). As the grapheme/phoneme relationship becomes less direct, learning to read a language becomes more difficult. English, because of its origins has developed a very complicated spelling system that is far less regular than other Latin based languages.

As neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene notes:

“One may wonder why English sticks to such a complicated spelling system. Indeed, Italians do not meet with the same problems. Their spelling is transparent: every letter maps onto a single phoneme, with virtually no exceptions. As a result, it only takes a few months to learn to read. This gives Italians an enormous advantage: their children’s reading skills surpass ours by several years, and they do not need to spend hours of schooling a week on dictation and spelling out loud. Furthermore, dyslexia is a much less serious problem for them.” 1

The Department of Education claims that 50% of the words in English can be sounded out – a figure that is commonly cited. Even if this is correct, students are still left with a written language in which decoding using phonics has no better than a coin-toss odds of success. This makes sounding out a very challenging guessing game. But the reality is that those who have studied English phonology have found that the actual percent of words that can be reliably sounded out is closer to 20%. Here are some of the findings from scholars who have studied the issue:

What do the experts say?

- Professor Godfrey Dewey, who devoted much of his career to studying our orthographical system, conducted a study in which he created a list of the 10,000 most common printed words out of a sampling of approximately 4,565,000 words. The result of this study, which he published in the book Relative Frequency of English Speech Sounds (Harvard University Press) was that approximately 1 in 5 of the most common words in English are spelled phonetically. He also found that for the 41 distinguishable phonemes, there are 561 spellings, the 26 letters of our alphabet are pronounced in 92 ways, and we also have 132 sets of two letters (digraphs such as th, ch, ea, etc.) that have 260 pronunciations. 2

- Professor Julius Nyikos of Washington and Jefferson College found 1,768 ways of spelling 40 English phonemes – an average of 44 per sound. He published his results in a paper called A Linguistic Perspective of Functional Illiteracy published by the Linguistic Association of Canada and the United States. He also found that these 40 English phonemes are spelled with all 26 single letters in the alphabet and at least 153 two-letter graphemes, 98 three-letter graphemes, 14 four-letter grapheme, and 3 five-letter graphemes, for a total of at least 294 different graphemes. (This is less than the 1,768 mentioned above because every phoneme is spelled with more than one grapheme. For instance, the “u” in the word “nut” can be spelled 60 different ways.) Professor Nyikos summed up the issue by writing, “It would be both ludicrous and tragic if it took lawsuits to jolt us into the realization that neither the teachers, nor the schools should be faulted as much as our orthography, which is incomparably more intricate than that of any other language. If English is not the absolute worst alphabetic spelling in the world, it is certainly among the most illogical, inconsistent, and confusing.” 3

- Professor Theodore Clymer studied phonics rules and published his results in a paper entitled The utility of phonic generalizations in the primary grades. Clymer collected 121 commonly used phonics rules. Using 2,600 words found in basal readers and Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary pronunciation guide, he compared the actual pronunciation of each word to the phonics rules that should apply and calculated a percentage of agreement. Eliminating any rules that did not apply to more than 20 words, Clymer whittled his list down to 45. Then, using 75% as a reasonable level of utility, he found that only 18 of the 45 rules had any utility at all. For example, Clymer found that the generalization commonly referred to as “when two vowels go walking” is effective only 45% of the time. 4

- Professor Robert Hillerich, the Chairman of the Dept. of Reading & Language Arts at the National College of Education did a study on vowels funded by the US Dept. of Health, Education & Welfare. The results were published in a paper entitled The Truth About Vowels. His conclusion: “From the evidence and the research studies reviewed, the author concludes that generalizations about vowels can be grouped into two categories: generalizations which hold true most of the time but which include too few words to be worth teaching, and those which apply to many words but which are so unreliable that they are not worth teaching.” 5

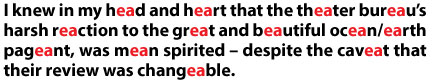

- Dr. Diane McGuinness, in her book Why Our Children Can’t Read explains the complex logic that is required to learn to read English and why that is a serious problem for students. Unlike most other alphabetic languages, there are tens of thousands of different syllables in English, with sixteen different syllable patterns.There are two or more syllables in most English words. Each syllable can have one of the sixteen syllable patterns and each vowel and consonant in each of these patterns can represent multiple phonemes.To get an idea of how complicated learning to “sound out” English is for a beginning reader, consider this one sentence where the very common “ea” vowel combination can be pronounced 13 different ways:

- Professors Max Colheart and Anne Castles published a comprehensive review of phonological awareness studies in the journal Cognition, titled “Is there a causal link from phonological awareness to success in learning to read?” They concluded that “no study has provided unequivocal evidence that there is a causal link from competence in phonological awareness to success in reading and spelling acquisition.” 7

| CV | CCV | CCCV | CVC | CCVC | CCCVC | CVCC | CVCCC |

| CCVCC | CCVCCC | CCCVCCC | CCCVCC | VCCC | VCC | VC | V |

| (C=consonant, V=vowel) | |||||||

Additionally, all 26 letters of the alphabet are silent in some words with no way of knowing whether a letter is silent or not in a word, and all letters except H, Q, U, W, X, and Y are doubled in some words and not in others, with no way of knowing whether a letter is doubled or not. The level of complexity is astounding. 6

- Professors Donald Hammill and Dr. H. Lee Swanson reviewed the National Reading Panel’s Meta‐Analysis of Phonics Instruction and found that “Instead of phonics approaches being superior to non-phonics approaches, we argue that the advantages of phonics instruction relative to non-phonics instruction have not been demonstrated.” 8

- Professor Jeffrey S. Bowers conducted an exhaustive and systematic review of 12 meta-analyses that assessed the efficacy of phonics and concluded: “There is little or no empirical evidence that systematic phonics leads to better reading outcomes … There can be few areas in psychology in which the research community so consistently reaches a conclusion that is so at odds with available evidence.” 9

Where does the “English is 50% phonetic” statistic come from?

The 50% figure comes from a 1966 study conducted by Professor Paul Hanna which was funded by the US Dept. of Health, Education & Welfare. The results were published in a paper entitled Phoneme-Grapheme Correspondences as Cues to Spelling Improvement. 10 Hanna studied 17,310 words selected from the Thorndike-Lorge Teacher's Word Book of 30,000 Words (omitting foreign words, trade names, slang, and rare words) and used Merriam-Webster dictionary pronunciation guide to create 203 phonics rules that were put into a computer.

Using these rules, Hanna input whole words and the computer achieved 49% spelling accuracy. However, citing this result to claim English is 50% phonetic is highly misleading for multiple reasons: 1) Hanna reached this number by allowing more than one grapheme per phoneme. If you allow only one grapheme per phoneme, English is only 20% phonetic. 2) Children are not computers and cannot memorize 203 rules. 3) Even if half the words were phonetic, children would still have no way of knowing which word is spelled phonetically and which is not. Imagine teaching arithmetic and telling children that 2+2=4 fifty percent of the time.

Why is English spelling so complicated?

English has evolved over the course of millennia, without any central planning. Words from Germanic Anglo-Saxon (woman, Wednesday) and Old Norse (thrust, give) were mixed with words from the Latin (annual, bishop), and Norman French (beef, war). Science, technology and the Enlightenment added words, often based on Greek (anthropology, phone, school), and wars and globalization added even more, like “verandah” from Hindi and “tomato” from Nahuatl (Aztec) via Spanish. Words from other languages typically carry their spelling patterns into English. So, for example, the spelling “ch” represents different sounds in words drawn from Germanic (cheap, rich, such), Greek (chemist, anchor, echo) and French (chef, brochure, parachute).

That English spelling is highly irregular is simply a fact teachers and students have to deal with. That’s why, throughout history, a veritable who’s who of English speakers have promoted the idea of reforming English spelling. These include Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Johnson, Noah Webster, Andrew Carnegie, Charles Dickens, John Milton, George Bernard Shaw, Mark Twain, H.G. Wells, Upton Sinclair, Theodore Roosevelt, Charles Darwin, and Isaac Asimov, etc. But the spelling reformers have yet to succeed, and to this day English spelling is incredibly challenging for children (and adults).

It’s because English spelling is so difficult to master that English is the ONLY language that has “spelling bee” competitions and a pronunciation guide in the dictionary.

English spelling is so irregular that dreaming up hypothetical spellings for words has become a kind of pastime. For example, Professors Dorothea Simon and Herbert Simon found that the word “she” could be spelled 36 different ways (the “sh” sound can be spelled 9 ways - TI, SH, CI, SSI, SI, C, CH, T, S - and the “e” sound in 4 ways E, EA, EE, IE). 11 And in what is probably the most famous example of orthographic gymnastics, in 1855 publisher Charles Ollier spelled the word fish as “ghoti” – taking gh from rough, o from women and ti from nation. (This example is frequently misattributed to George Bernard Shaw.) 12

But while these examples are amusing, just consider how confusing it must be for a child first learning the written language. To get an idea of how complicated learning to “sound out” English is for a beginning reader, consider this one sentence where the very common “ea” vowel combination can be pronounced 13 different ways.

Put simply, if phonics worked as it should, the word would be spelled “foniks.” So while kids do need to learn how our written language represents our spoken language, the use of explicit phonics instruction to teach them to read with fluency and comprehension will always be very challenging for students.

1“Reading in the Brain: The Science and Evolution of a Human Invention” by Stanislas Dehaene https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/6719017

2“Relative Frequency of English Speech Sounds” by Godfrey Dewey https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674419193

3“A Linguistic Perspective of Functional Illiteracy” by Julius Nyikos Published by the Linguistic Association of Canada and the United States, Volume 14 https://www.lacussquare.org/

4“The Utility of Phonic Generalizations in the Primary Grades” by Theodore Clymer https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ540711

5“The Truth About Vowels” by Robert L. Hillerich https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED089252

6“Why Our Children Can’t Read” by Diane McGuinness https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/700291.Why_Our_Children_Can_t_Read_and_What_We_Can_Do_About_It

7“Is there a causal link from phonological awareness to success in learning to read?” by Anne Castles & Max Coltheart https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14711492/

8“The National Reading Panel's Meta-Analysis of Phonics Instruction” by Donald Hammill & Lee Swanson https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-22028-003

9“Reconsidering the Evidence That Systematic Phonics Is More Effective Than Alternative Methods of Reading Instruction” by Jeffrey S. Bowers https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10648-019-09515-y

10“Phoneme-Grapheme Correspondences as Cues to Spelling Improvement” by Paul Hanna & others https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED128835

11Alternative Uses of Phonemic Information in Spelling” by Dorothea P. Simon & Herbert A.Simon https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED063295

12“Ghoti” by Ben Zimmer https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/27/magazine/27FOB-onlanguage-t.html